Written by Wen-Hao Wang, Photo by Yu-Jong Peng and Wen-Hao Wang,Translated by Adam Tyrsett Kuo

“Everything you see on this pig farm has Taiwanese influences,” said Yen Lung-fang, a Burmese Chinese pig farmer. Knowing that we are reporters from Taiwan, Yen, who usually keeps to himself and does not allow visitors on his farm, gives us a very warm welcome.

The pig farm is a product of Yen and his cousin Wang Chi-yi’s training in an Overseas Community Affairs Council-organized program at the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology more than a decade ago.

Yen and Wang, both 38, named it the “Five Hill Farm,” which is located 40 kilometers north of Myanmar’s biggest city, Yangon, in a village along the Mandalay Expressway.

The scale of the Five Hill Farm is equivalent to a middle-sized pig farm in Taiwan, but in Myanmar, Yen and Wang’s farm ranks third in terms of size, after the state-owned pig farm and the pig farm owned by Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Group. Looking at the Five Hill Farm’s operations and facilities, one sees a great deal of Taiwanese influence.

Their experience in Taiwan has been crucial to their ability to rival state-owned and corporate farms as independent farmers.

When it comes to consumer behavior and pork, one finds a lot of interesting differences between Taiwan and Myanmar.

In Taiwan, there has recently been a lot of commotion over the spike in pork prices. The uproar stems from the fact that pork has long since become a part of everyday meals. Not having pork on the dinner table, not having strips of pork to stir-fry with vegetables is considered to be something of a disappointment.

In the past, when people had lower levels of income, pork was only served at weddings or used as offering at funerals, but as people became wealthier, pork came to be as abundant as rice and vegetables — even leading to concerns about overnuitrition. The increase in supply can be attributed to advances in pig farming over the past four decades, a result of the transformation from families raising pigs to an institutionalized business. And during this process, white pigs with a higher feed conversion ratio have gradually replaced black pigs, making supply of the latter scarcer (and therefore pricier).

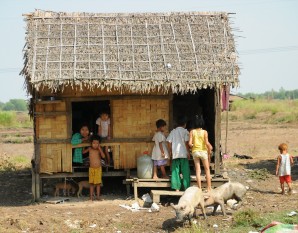

Visiting Myanmar is a bit like traveling back in time. In villages, apart from growing rice, families also keep two or three black pigs, chickens and ducks, which run freely around stilt houses. And when farmers need cash, they chase down their pigs, tie them up and head off to the market on their motorcycles.

In Myanmar, white pigs are not as common as their black pigs counterparts and are therefore more expensive. Wealthier farmers generally keep roughly a dozen white pigs in pens on the sides of lakes or fish ponds, using pig manure to feed the fish, a practice that decreases cost and lessens pollution. There are, however, very few who raise pigs in accordance with a standardized set of operating procedures.

Pigs raised this way still account for over 70 percent of the pork supply in Myanmar. The fatty black pigs are an important source of cooking oil in the Southeast Asian country. With an unstable supply of electric power, refrigerators are not common in Myanmar. Cooked pork is generally preserved between thick layers of fat, making the fat rich black pig an indispensible consumer good, driving not only the price of lard but also pork upward. Things are different in Taiwan, where people like to eat lean meat.

Overall, consumer spending is still very limited in Myanmar, and most people rely on freshwater fish and chicken as their main source of protein from meat. But as economic development has picked up, so has the demand for pork. And eying this trend, Yen and Wang leveraged the skills they learnt in Taiwan to claim a portion of the market in Myanmar.

Training in Taiwan

ust after Taiwan’s pig farming industry had weathered the foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, Wang, Yen and four other Burmese Chinese signed up for a training program organized by the Overseas Community Affairs Council in 1998. All six chose to learn about animal husbandry and took courses at the National Pingtung University of Science and Technology (NPUST).

We’ve chosen animal husbandry, but what do we want to raise? Chickens, pigs, or cows? Wang and Yen assessed the overall situation before they left for Taiwan and found that in Myanmar the pork was more expensive than the chicken, and although the chicken was a more affordable type of meat, the market was dominated by Thailand’s Charoen Pokphand Group. Beef, on the other hand, was not commonly eaten by farmers and their families. Given that the pork industry was still at an early stage of development, it seemed to offer promising opportunities.

Of the six Burmese Chinese students, Wang and Yen decided to learn about pig farming, whereas the remainder chose to learn about raising broilers and egg-laying hens.

Wang recalled that during the two-year program, apart from attending lectures on theory, they were also brought to pig farms in Changhua and Nantou to learn about managing a pig farm, covering areas such as pigpen planning, feed mixing, breeding, disease prevention and control, manure management, biogas power generation and business management, all of which had to be learnt in a short span of two years. Although they had a tough curriculum, they learnt a lot, which later proved to be beneficial to their business venture.

Pig farming in Myanmar is not as convenient as it is in Taiwan. Yen said that although Myanmar has good breeds of pigs and chickens, the country lacks the equipment for raising livestock, unlike Taiwan, where the necessary equipment and facilities come complete. All you need to do is dial a number, and you can get companies to set it up for you, he added.

In Myanmar, you have to procure and assembly all the equipment by yourself. It isn’t feasible to replicate Taiwan’s model in Myanmar due to several factors such as cost. Yen explained that one needs to adapt to the actual circumstances in Myanmar in order to strike a balance in terms of cost and practicality.

Faced with frequent power outages, Yen and Wang decided to generate power from biogas. In Taiwan, the government encourages pig farmers to install equipment for generating biogas power, but because of limited land mass and the fact that power can be bought inexpensively, this approach hasn’t had much appeal among Taiwanese pig farmers.

In Myanmar, power outages are very common, but using biogas to generate power is an effective solution. Wang and Yen’s Five Hill Farm, for example, can produce a steady supply of power for more than 17 hours per day, and the residual wastewater can be reused to water crops and the more than 900 palm trees on the farm.

By applying the things they learnt in Taiwan, they have been able to make use of virtually all their resources.

Overcoming Obstacles

After more than a decade, Wang and Yang’s Five Hill Farm has expanded to become the third largest pig farm in Myanmar. Yangon’s largest state-owned pig farm has 2,000 sows, followed by Charoen Pokphand Group’s farm with 500 and the Five Hill Farm with 400.

On average, one sow delivers 10 piglets, meaning that the Five Hill Farm raises around 4,000 pigs, which is the equivalent to the size of a typical Taiwanese pig farm with 2,000 to 5,000 pigs.

It wasn’t always smooth sailing for Wang and Yen. Slaughterhouses, for example, refused to buy their pigs in an attempt to drive prices down. Wang said that Myanmar doesn’t have a transparent auctioning system and that prices are directly negotiated between slaughterhouses and pig farmers. Because slaughterhouses exercise control over distribution channels, pig farmers are at a disadvantage in negotiations.

In a bid to bring pork prices up to reasonable levels, Wang and Yen decided to finance their own slaughterhouse and distribute their pork by themselves. Once the slaughterhouses saw that the Five Hill Farm was capable of running its own facility, they began to worry about losing their edge. As a result, the slaughterhouses gave up on trying to keep pork prices low and decided to cooperate with Wang and Yen’s farm instead.

After more than a decade, Myanmar’s pork market is seeing changes. Last year, pork prices were better than that of chicken; however, Wang said that the market currently isn’t big enough and that one needs to make careful assessments before making large-scale investments in Myanmar’s pig farming industry.

As for Taiwan-based businesses that are interested in selling their equipment in Myanmar, Wang suggested that they should wait for a better timing to enter the market, because large-scale farms are already adequately equipped and there aren’t many small-sized farms that are able to afford the equipment yet.

There is, however, great potential in the animal vaccine and processed meat markets, because these products are mainly made by the Charoen Pokphand Group or imported from mainland China, Wang said, adding that the supply doesn’t meet the demand. Especially meat processing, because as consumption grows in Myanmar, and with the arrival of international food brands such as KFC and Lotteria in Yangon, the demand for processed meats like bacon and ham will increase.

It has been six years since Yen and Wang last visited Taiwan, but they both have a special connection to the island, because it was due to the OVAP’s training program that they were able to set up a successful business in Myanmar later.

In Taiwan, the Royal Poinciana blooms during the graduation season, and in Myanmar, one can find the flamboyant tree almost anywhere. The lives of Yen and Wang can be likened to the Royal Poinciana. They graduated in Taiwan and used what they learnt on the island to start a brilliant business in Myanmar.