Written by Yu-Jong Peng,Photo by Yu-Jong Peng ,Translated by Amy Feng

It was the end of May, 2013. Irrawaddy Delta was hot and humid with the temperature over 40 degrees awaiting the arrival of the monsoon season.

At the end of our investigation on agriculture and a full month of interviews in Myanmar, I have finally arrived in Pathein, the rice capital of Myanmar located 150 km from Yangon. Pathein, perhaps we could even call it the largest rice center in Asia, is the capital of Ayeyarwaddy.

To tell the truth, it was because I was fortunate enough to have come here and interviewed “Metta,” the largest grassroot NGO in Myanmar, and the villages and villagers that had received assistance from Metta, that I had regained some hopes from Myanmar despite my pessimism regarding its rapid reform and opening and its wholehearted embracement of economic liberalization. After a whole month of journey in Myanmar seeing how large agricultural corporations and financial groups grabbed lands from small farmers, and foreign seed corporations, animal husbandry seeding factories, and feed companies carved territories everywhere, it was worrisome as to where this pattern and style of development would lead Myanmar. Will the people at the bottom benefit from it?

Standing by the shore of Bassein River, we looked at these brand new high-tech temperature-controlled rice and grain equipment in contrast with the images of the villagers in villages that don’t even have electricity or running water. We couldn’t help but felt sad and pessimistic. However, our worries were temporarily subsided by the sunny smiles of Saw Nay Baluhdu, who came to welcome us as a staff of Metta.

The Grassroot NGO from the Soil of Myanmar: Metta Development Foundation

The person who came to welcome us was Saw Nay Baluhdu. He was from one of Metta’s training centers called Sing Guang Training Center that was located in Sing Guang Village in Ayeyarwaddy Region. Metta is the largest grassroot NGO in Myanmar.

Metta Development Foundation is the largest grassroot NGO organization receiving high praise and respect from the poor farmers in Myanmar. In the past 15 years, it has assisted in the growth and development of more than 100 villages, and helped more than 30,000 small farmers invest in sustainable agriculture, or, organic or natural farming defined broadly, that increased harvest and stabilized income.

Metta started as a small entity with only 6 people in 1998 and evolved into an organization with more than 500 full-time employees presently in 2014. Its annual operation cost is about 9.4 million U.S. dollars and this money comes exclusively from domestic and international donations. It provides assistance in 6 areas of work in hope of developing a civil society with villages as its base unit in remote regions and villages all over Myanmar. The 6 areas of work are: agriculture and forestry, education, health, livelihoods, emergencies, and development and capacity building.

Metta was established in 1998. After seeing too much stagnation and too many farming communities fall into a vicious cycle of debt and poverty as a result of ethnic and religious difference as well as internal conflict, the founding members of Metta were aspired to promote internal peace, trust among ethnic groups, and development in agricultural community. They named the organization Metta, which means loving and kindness in Buddhist text in Burmese, ancient Balinese and Sanskrit languages, to begin an inspiring journey of selfless devotion for the benefit of the farmers.

Two Mechanisms for Developing Farming Community: 1) Participatory Action Research (PAR)

Participatory Action Research (PAR) and Farmer Field School (FFS) are the two mechanisms that Metta developed to assist farming communities in its development and growth.

負責Metta生計/生活(livelihood)部門的 Sa Wai Ziw Aung,正在向我們解釋 Metta獨特的村民參與式研究(Participatory Action Research,PAR)方法

Sa Wai Ziw Aung, who was in charge of the Department of Livelihood in Metta, explained to us during an interview in Yangon that PAR referred to members of each village gathering together and discussing issues with the guidance from someone from Metta, known as the Facilitator. A Facilitator provides guidance to villagers who conduct investigations in resources and self-evaluations, make analysis on advantages and disadvantages, and list issues desired to be resolved or directions for development. They then write down action plans; for example, xyz village is suitable for raising pigs, chicken and ducks, planting chysamsumums, or desires to develop micro-village credit loans. This method helps identify the actual needs of a village. A plan written using this process is called a “PAR Plan.”

In carry out the plan, Metta encourages villagers to be decision-makers. Having villagers elect executive and managing committee members not only promotes trust and overall participation of the villagers but also increases the chance for the plan to become successful. Take the following scenario as an example. The whole village would gather together and discusses how to set up a village fund to support some families who would be starting a pig farm to improve their livelihood and food security. Metta’s Facilitator would offer consultation and guarantee that the funding would be revolving. In other words, when villagers apply to join the pig farm plan, the committee representing the villagers would discuss and decide on which family to receive the funding. Then, the village fund would be dispersed in the form of low-interest rate loans while Metta would provide necessary technical assistance. When the pig farm plan had been successfully carried out, part of the interests from the loans would be returned to the village fund, and other families that needed to improve their livelihoods would be selected to participate in the plan in the following year.

Sa Wai Ziw Aung explained further that a PAR Plan emphasized participation because only when villagers actually participated in the discussion that transparency and accountability could be achieved. For a sustainable and balanced development in villages to continue, it is essential to train villagers to develop a habit for group discussion, plan execution, and review and evaluation that they will continue to do even when the PAR Plan has ended. But for Metta, it is not only the participation but the quality of participation that is important. For example, can villagers develop a habit for spontaneous discussion? During discussions, are women afforded the same level of representation as men? These are also issues that Metta attempts to address.

According to Metta’s annual statistic report, taking year 2008 as an example, there are more than 3,000 villagers in Myanmar participating in Metta’s PAR work station. Among them, 195 were selected to receive the 3-month long training program known as Training for Trainers, or TOT. Resulting from the training, 43 villagers stayed and became Metta’s full-time employees. From this example, one can infer that Metta has never been an organization that situated at the top to “lead” the farmers. It has been a grassroot and organic organization that has worked closely with and learn together with the villagers. It encourages and welcomes farmers to become part of the organization.

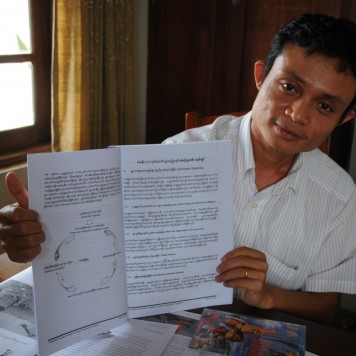

在伊洛瓦底省來接待我們的 Metta 工作人員 Saw Nay Baluhdu 就是受基礎訓後留下成為員工的人之一;今年37歲的Saw Nay Baluhdu勃生大學畢業後,參與訓練者培訓課程(Training for Trainer,TOT)後加入Metta,留在故鄉協助村落與農民發展;2012年也獲得Metta資助,到印度考察,學習農民留種、基改種子對農業的威脅、自製有機肥等等。

Saw Nay Baluhdu, who came to welcome us in Ayeyarwaddy Region, was one of the trainees who joined Metta. He was 37 years old. After graduating from Pathien University, Saw Nay Baluhdu joined the Training for Trainers program and then joined Metta to stay in his hometown helping the farmers making improvements in the village. In 2012, he received support from Metta to visit India and studied issues of seed saving, the threat of genetically engineered seeds to agriculture, and how to make organic fertilizer.

Saw Nay Baluhdu rode motorcycle and took us into the deeper part of the Delta to meet with villagers from the Tharatcho Kone village, which was located about one-hour car ride from Pathein. The main religion in Tharatcho Kone Village was Christianity. It had about 400 people with the average age being 50 years old. (This village has an extremely aging population given Myanmar is a country with young population.) Metta initiated PAR plans here, operated a 4-month long Farmer Field School, and assisted 13 villagers in setting up a Seed Bank collaboratively for self-seeding and purifying wetland rice seeds. Following these initiatives, Saw Nay Baluhdu organized 30 villagers to establish a microcredit loan program with each person giving 1 U.S. dollar (1,000 Kyats) to join. After a few yearly cycles, the fund had about 1,500 U.S. dollars. For a small and poor village in Myanmar, this was not a small fund. It was enough to fulfill the extensive needs of those villagers who applied for assistance in education and agricultural programs.

A villager named Saw Roldland made a point of grabbing a handful of the rainy season rice seeds saved in the Seed Bank to share with us. He then took us to see his land that he just finished harvesting and told us about how he learned the importance of controlling self-seeding while at the Metta workshop. He complained about the flooding problem during the rainy season caused by inefficient irrigation system. He also talked with excitement about how he hoped to stop relying on expensive chemical fertilizer when this field would become organic planting next year.

In here, I learned about how Saw Nay Baluhdu stayed in his hometown as a Metta Facilitator to contribute his knowledge and expertise to the development of the village. I saw how he worked together with the villagers to empower themselves at Tharatcho Kone and promote mutual trust. I also witnessed a growing awareness of self-autonomy among farmers and citizens with a firm foundation. These experiences, together with my encounters with such a democratic and energetic grassroot organization basing its foundation in village communities, have made me less pessimistic about Myanmar’s complete embracement of liberalization.

Metta’s other mechanism for village development: 2) Farmer Field School (FFS)

Metta’s other important mechanism for village growth is Farmer Field School (FFS), which began in the lowland villages in Keqin Region in northern Myanmar in 2001.

Khin Maung Latt, a senior employee of Metta and Metta’s Agriculture PM, explained during an interview at the Yangon headquarter that the aims of FFS included promoting food security in remote villages and improving farmer’s ability to control and manage crops and fields through training.

Khin Maung Latt explained it further that Metta hoped to facilitate, coordinate, and empower villages and villagers. A FFS would be made up by 20 farmers in average. They would gather together for half a day for class every week during the entire rice cultivating season (around 4 months during the rainy season). During this period, Metta’s Facilitator would work in the fields together with the farmers. Following the instructions in the Farmer Field School Facilitator’s Handbook, the Facilitator would share techniques and knowledge regarding selecting types of rice crops, planting and nurturing seedlings, planting methods, water level management, soil nutrient, problems of pests, and so on. They would assist small farmers in practicing sustainable farming (or natural or organic farming as broadly defined) to increase harvest and stabilize income. Similar FFSs would be afforded opportunities to learn from each other through visits. During harvest time, each FFS would hold a Field Day event, and invite local officials, village seniors and villagers from neighboring villages to come. FFS would share what they had learned with the visitors to gain more willing participants.

Assist highland farmers in getting rid of opium cultivation while till the land for grassroot democracy

In recent years, Farmer Field School has spreaded to the upland-rice-growing highland area in Shan and Kayah of eastern Myanmar. It has successfully helped many opium-growing farmers transform from relying on narcotics plants for profit to securing stable income by other means. It has also helped many refugees displaced by ethnic violence or internal conflict become self-reliant through farming.

From 2001 to 2013, Metta’s Farmer Field School (FFS) trained 772 Facilitators, established more than 1,300 FFS in numerous states, and trained 33,700 farmers (of which more than ¼ were women farmers). It was able to increase rice production using almost none of the chemical-based fertilizers or pesticides. Many villages that had FFS went on to establish rice-grain banks, seed banks, buffalo banks, microcredit loans, and co-operative stores. After the basic livelihood was stabilized, some of these villages even successfully developed suitable cash crops such as vegetable, tea, coffee, chrysanthemum, sericulture and silk production, etc.

The vision of Metta stipulates that Farmer Field School is not only for improving livelihood in farming villages but also the primary entry point for community development that creates solidarity, promotes ethnic harmony, nurtures grassroot democracy.

We have witnessed the realization of this vision in a small village in Irrawaddy Delta.

Following the Bassein River, Saw Nay Baluhdu took us deeper into the Delta on a boat ride. We came to a village named Phayachaung. Phayachaung just had its FFS in 2012. The villagers gathered inside the meeting place next to the stupa near the shore of the river. They sat cross-legged and discussed with those of us from Taiwan about issues and current conditions regarding agriculture and farming villages in Taiwan and Myanmar.

A villager named Ko Thant Zin Oo and another one named Ko San Win were especially interested in learning about the snail damage and control in Taiwan and the types of support that the government gave regarding organic farming. Another villager named Ko Aung Win, on the other hand, was curious about whether or not the villages in Taiwan felt the same way as his own about deterring their offsprings from engaging in agricultural work. This topic sparked heated discussions among the villagers. In my observation, the villagers of Phayachaung spoke enthusiastically. Regardless what the topics were, be it about Taiwan’s production and marketing system, price, fertilizers, merchandise, or the current conditions on organic farming and the difficulties encountered when making transitions, these villagers spoke openly about the topics, asked follow-up questions, and discussed the topics. There was no such thing as being too shy to speak up in these open discussions. Different ethnic groups, such as Burmese and Karen people, could also discuss issues without being obstructed (where many of these ethnic groups were still holding hatred against each other in other parts of Myanmar.) They were obviously very familiar with the practice of open expression and group discussion. To find this type of democratic quality in existence so naturally and normally in such a small village in Irrawaddy Delta made a great impression on me.

Daw Lahpai Seng Raw, the founder of FFS and former CEO of Metta, wrote in the Farmer Field School Facilitator’s Handbook the following words: “The Farmer Field School is not only meant to increase the production and quality of the small farmer through technology and knowledge transmission. More importantly, it is meant to be the primary entry point for community development that farmers from different ethnic or social groups can gather together for learning, working, experiencing, planning, and executing the plans cooperatively. After the FFS is over, these farmers will bring back knowledge, experiences, and techniques to their own villages. They will each establish respectively seed and buffalo banks, make plans for village funds and microcredit loans, create cooperative stores, or develop other creative methods for improving economic conditions and quality of life.”

These inspiring visions and practices that promote mutual trust and peace among ethnic groups have been quietly realized in various extremely remote farming villages in Myanmar. Only with peace and mutual trust that a grassroot-based civil society can take root, and Myanmar can enjoy sustainable development from which the middle class and underclass people can also benefit.

Daw Lahpai Seng Raw, an ethnic Kachin, is one of Metta’s founder and its former CEO. She received The 2013 Ramon Magsaysay Award, often considered Asia’s Nobel Prize, because of her and Metta’s contribution to Myanmar’s poor farmers. At the award ceremony speech, Daw Lahpai Seng Raw donated all the prize money and called the attention of those present to the 287 ethnic minority families in 4 villages and the natural environment that would become affected by China and Myanmar’s joint Myitsone Dam project in northern Myanmar. At the same time when Myanmar is transitioning from close to open and experiencing an economic take-off, its civil society is also taking root like still waters run deep.

Related Links:

緬甸Metta發展基金會的官方網站,年報與研究報告資料相當豐富

http://www.metta-myanmar.org

緬甸Metta發展基金會創辦人之一、前任執行長Daw Lahpai Seng Raw(Kachin,克欽族),因為她與Metta對於緬甸貧農的貢獻,在2013年獲頒有亞洲諾貝爾獎之稱的麥格塞塞獎

http://www.rmaf.org.ph/newrmaf/main/awardees/awardee/profile/347

Daw Lahpai Seng獲頒麥格塞塞獎的得獎感言,不忘呼籲關注,並捐出所有獎金,投入協助保護緬甸北部、受中緬合資密松大壩興建計畫而影響的4個村子、287個少數民族家庭與自然環境。

http://www.rmaf.org.ph/newrmaf/main/community/blog/all/1/view/14